Lessons Learned From Shorting Amazon

Although I have an MBA, my learnings about investing come from Charlie Munger and Warren Buffett, Vice-Chairman and Chairman of Berkshire Hathaway Inc. I have attended Berkshire Hathaway shareholder meetings about dozen times and the four basic rules of investing that I have learned are:

- Do you understand the business you are buying (think of buying stock of a business like buying the entire business)?

- Can you predict the earnings of the business for the next five to ten years?

- Does the business have a competitive advantage (i.e. does the business have something that a competitor would find hard to copy)?

- Is the stock fairly priced?

|

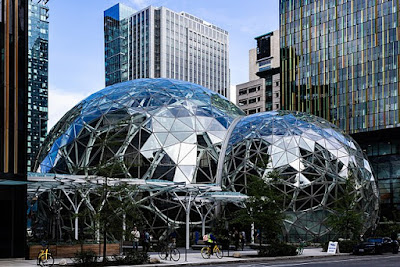

| Amazon headquarters in Seattle, WA. Photo Credit: Wikipedia |

These four rules are easy to understand and hard to implement. A few years ago, when Amazon stock was trading below $300 and its P/E (Price to Earnings ratio), which is one way to determine if the stock is fairly priced, was above 2,000. At the time, The S&P index P/E was less than 20 at the time. I felt that the stock was way overpriced. So, I applied the four rules:

- Understanding the business: I did understand ecommerce. Amazon Web Services (AWS), which is a subsidiary of Amazon focused on providing cloud computing services, was less than 3% of Amazon revenue at the time so I ignored it. I like Amazon as a customer. They are innovative and customer-focused. However, as an investor, I saw them as a highly overpriced stock.

- Predicting the earnings: For the most part, I could predict that Amazon would continue to grow because the broader trends were in their favor i.e. shopping was moving online. Amazon wanted to expand internationally and with new shopping categories. So, I predicted that earnings would continue to grow but margins wouldn’t change drastically.

- Competitive Advantage: During the time of my analysis (2012-2013) Amazon did have a huge competitive advantage. It would have been very hard for any company to replicate what Amazon had - customer mindshare, supply chain network, supplier relationships, online marketplace, etc.

- Fair value: How do you determine if a stock is fairly priced? The Berkshire model is to understand the intrinsic value of the company. Intrinsic value is hard to calculate but you can get a general idea based on an understanding of the business, predictability of future cash flows, interest rates, etc. A stock is considered fairly priced if it is trading close to its intrinsic value. In Amazon’s case, any way you looked at it, the stock was trading way above its intrinsic value.

My hypothesis that Amazon would continue to grow but have similar levels of earnings so the stock would eventually come down in price. I was relatively new to the world of value investing and the idea of a company trading at ~3,000 P/E bothered me. I decided to short Amazon (shorting is a mechanism where you are investing in the idea that the stock will go down in price). My exact words to my friends were, “I am shorting Amazon on moral grounds.” In other words, emotions played a key role in the decision.

I closed most of the short position around $600 but I kept the position partially open hoping that the stock might go down. Eventually, I closed all positions. Final positions were closed above $1,000.

How could that happen? Needless to say that I lost a lot of money on this one trade and this one bad decision overshadowed multiple good decisions I made. A good thing about big mistakes is that you learn big lessons that you don’t forget. Following are my lessons learned:

- Understand Context

When Buffett and Munger talk about investing, they do not say that if a stock does not follow the four rules, short it. They suggest not to invest in that stock. It is true that Amazon was overpriced at the time of my investment decision but I did not consider the possibility of a scenario where Amazon can grow into that valuation. Amazon P/E is close to 100 today.

I completely ignored AWS in my analysis and almost of all of Amazon earnings have come from AWS in the last couple of years.

Buffett and Munger teachings are applicable to companies where the nature of the business and earnings does not change drastically in five years and one can predict earnings for the next ten years (in ballpark amounts). Their idea is to buy the stock and forget about it. My approach to Amazon was to short the stock and forget about it which was wrong. Since Amazon’s business is dynamic in nature, I should have validated my decision to short, every quarter when Amazon provided new data in quarterly earnings report. When you buy a stock and it does not go up, you don’t lose money. When you short a stock and it does not go down, you lose money.

The main lesson is to see and understand in which context your learnings are applicable.

- Don’t be overconfident

Before my decision to short Amazon, all my investment decisions have been successful (including shorts). Past success gave me confidence to short Amazon. I think a good investment partner would have been helpful who could question me on my assumptions and find holes in my hypothesis. It is easy to fool yourself. If I was not overconfident, I would have done more homework and spent more thinking what if I am wrong.

The main lesson is to approach investment decisions from a beginner’s curiosity and understand all the scenarios in which you could be wrong.

- Don’t give into the desire to be right

After the stock doubled to the price at which I shorted it, I should have closed all the positions because my hypothesis was being invalidated. However, I only closed half the positions and instead of validating my assumptions and looking at everything from fresh eyes, I hoped that the market will agree with me at some point in future. What was driving my decision was not the desire to not lose money but the desire to be right. Munger calls it inconsistency-avoidance tendency that causes human misjudgement.

The lesson is to not get emotionally attached to decisions you made and constantly evaluate your decisions objectively with no desire to be right.

These lessons apply not only to investing but to decision making in general. This mistake has made me a better investor and a better decision-maker. I hope that you can learn these lessons without losing money.